|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PVT RICARDO DE LAMA’S MILITARY SERVICE IN WWIIAN OVERVIEW*

Camp Fannin, located at Tyler (TX), was an Infantry Replacement Training Center (IRTC), which could handle up to about 20,000 troops at a time. After four months spent in infantry training at the IRTC and three additional months of stateside training, presumably in an Infantry unit, on 18 March 1944 he was sent overseas as an individual replacement, destination North Africa. This length of time between induction and overseas assignment as an individual replacement was typical at the time: faced with a very serious replacement shortage for overseas units (notably infantrymen), in February 1944 the War Department had decided to strip stateside units of soldiers with a minimum of six months of training to send them overseas. This resulted in an average of 48,000 replacements being shipped overseas each month, and since Ricardo de Lama was older than eighteen, and was not already a father before Pearl Harbor, he was one of the first to leave within this new replacement policy. A few months later, even the minimum six months of service policy was abandoned, and replacements were sent overseas straight after four months of RTC training. This individual replacement system in the case of the Infantry meant soldiers often found themselves assigned to units in the mid of combat operations, with no chance to acquaint themselves with their comrades and frontline conditions. In practice, this translated into a very high casualty rate among replacements. Conversely, this system of maintaining units in action indefinitely through a stream of individual replacements, also had the effect that combat soldiers lived in a doom-like world were they were kept fighting till wounded, killed, or otherwise disabled, with obvious mental and physical consequences. Within US Army organization of that time, Company G was one of three rifle companies in the second battalion of an infantry regiment. Each infantry regiment was organized on three rifle battalions and supporting units, each rifle battalion in turn comprised the HQ Company, three rifle companies, and a heavy weapons company armed with water-cooled .30 cal. M1917A1 machine guns and 81 mm mortars. Other supporting weapons, such as .50 cal. M2HB machine guns and 2.36” rocket launchers (“bazookas”) were also available. The three rifle companies in the first battalion of a regiment were coded A, B, and C, with the HW company being D. The second battalion was similarly organized on E, F, G, and H companies, and the third on I, K, L, and M companies. In US Army radio alphabet of that time, these letters translated into Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog, Easy, Fox, George, How, Item, King, Love, and Mike. Infantry rifle companies (with a strength of about 190 men) included the company headquarters group, three rifle platoons, and a heavy weapons platoon with two air-cooled .30 cal. M1919A4 machine guns and three 60 mm M2 mortars. The rifle squad, of which there were three per rifle platoon, was the basic fighting unit of Infantry organizations: twelve infantrymen, usually armed with cal. .30 M1 semiautomatic rifles and one cal. 30 Browning automatic rifle. In combat, veteran units could and did modify this prescribed organization, adding different types of weapons and, when available, overhead personnel. The 34th Infantry Division, originally a federalized National Guard division from Iowa, Minnesota, and North and South Dakota, was the only US Infantry division serving in the North African and Mediterranean Theaters of Operation throughout the war, the only other US division with a similar combat record being the 1st Armored Division. The 34th, which went to Northern Ireland in January 1942, was also the first US Army division sent overseas after Pearl Harbor (i.e., excluding units already stationed in the Pacific). Together with the 1st Armored, the 34th had provided most of the volunteers for the first Ranger Battalions formed by the US Army in WWII. Then, it fought in North Africa and mainland Italy, where the Division finished the war near the Alps in May 1945.

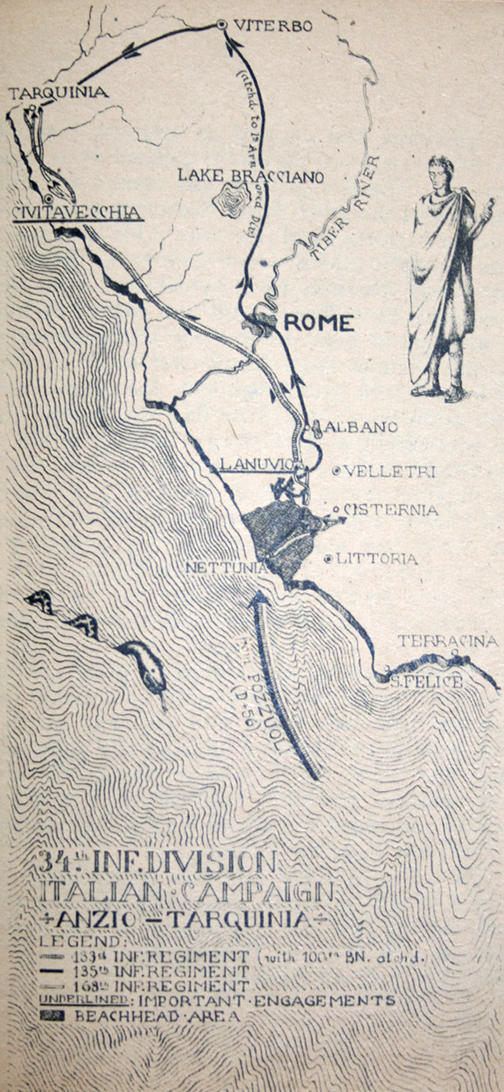

The Trail of the 34th Infantry Division in WWII (34th Inf.Div.)] Pvt. de Lama, as a combat infantryman, had taken up the most dangerous job in the US Army at war. Altogether, the 34th Infantry Division suffered 4,300 battle dead (soldiers who were killed in action or died of wounds received in action), and 11,545 wounded in action. Of the above battle deaths, 3,825 (with a proportionate share of about 10,000 wounded) occurred within its three Infantry Regiments, which at full strength (as seldom happened in Italy) comprised about 9,600 soldiers. This means that, not counting accidents, illnesses and diseases (which, on average, in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations accounted for more than 300% of battle casualties), battle casualties alone statistically accounted for one and a half complete personnel turnover in Infantry regiments within the Division during its combat cycle. Considering the daily averages of personnel in the division’s fighting echelon, the 34th division’s casualty rate has been evaluated as the highest of any division in the war against Germany. Rome to the Arno, June - August 1944At the beginning of June 1944, the 133rd was engaged south of Rome, participating in the Allied offensive, which had broken the stalemate along the Gustav Line at Cassino and at the Anzio beachhead, where the 34th Division had landed in March 1944.

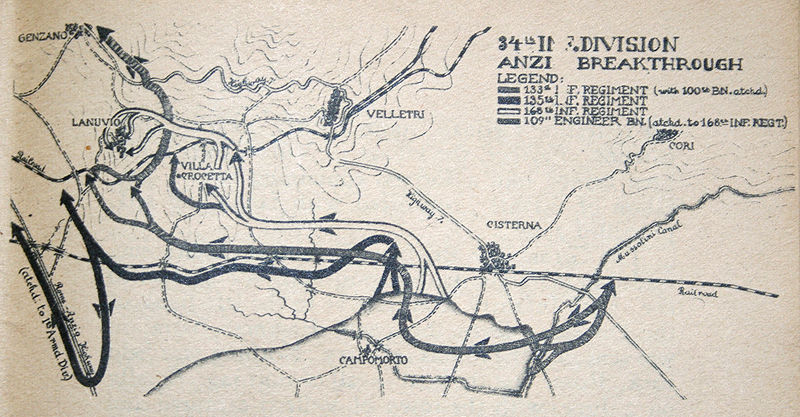

34th Infantry Division: Anzio Breakthrough (34th Inf.Div.) Pvt. de Lama’s introduction to frontline duty was not easy. The objective was taken, but the advance was slow and the 2nd battalion had 12 KIA’s, none however in Company G. The Regiment was then shuttled to Civitavecchia, the main port city in the Rome area, which fell to the 133rd on 8 June 1944 with little or no opposition.

34th Infantry Division: Anzio – Tarquinia (34th Inf.Div.)

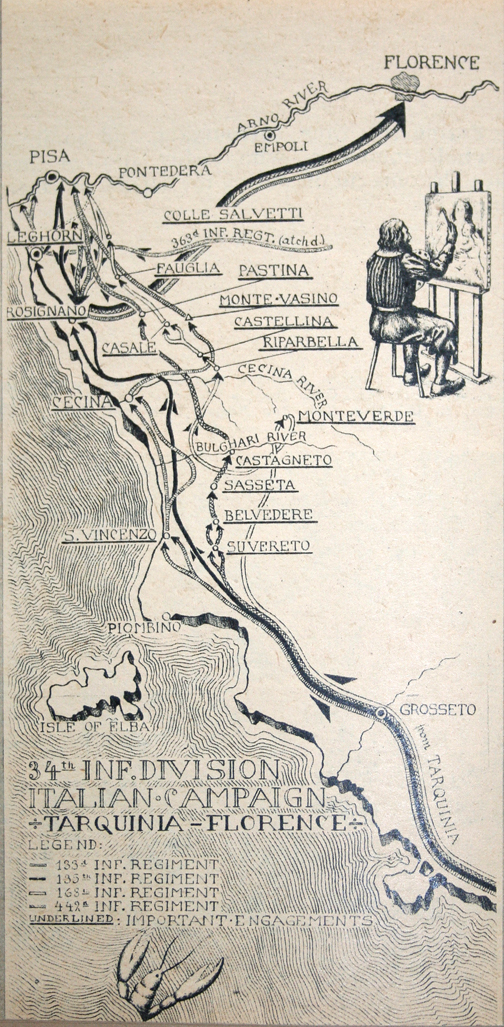

When the 34th reentered the lines along the Tyrrhenian coast at the end of June, the Allied advance had reached Tuscany, with the immediate objective of gaining the Arno river line and the large port facilities at Leghorn. On 26 June 1944, the 133rd was back into combat and attacking near Piombino, a coastal port town about 40 miles south of Leghorn.

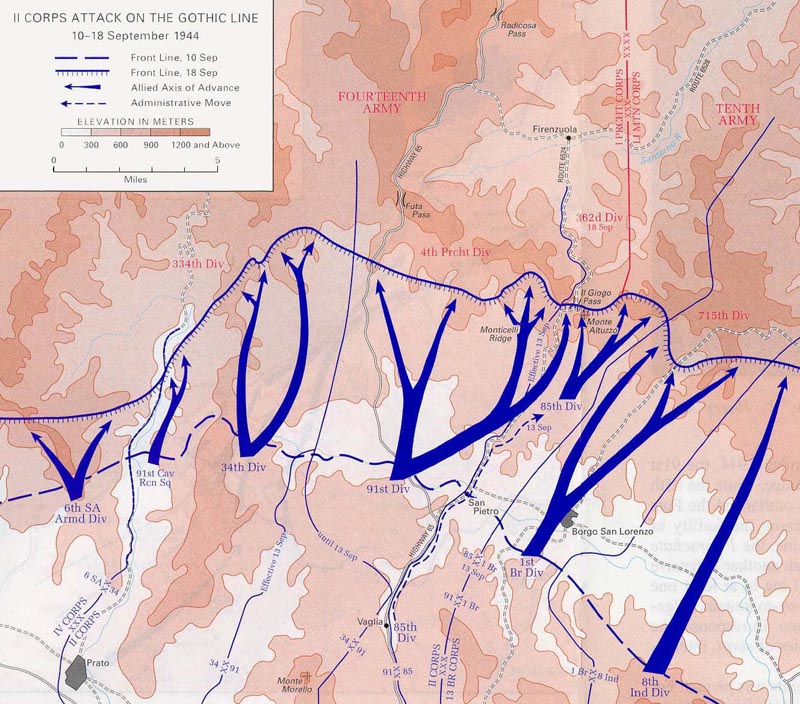

34th Infantry Division: Tarquinia – Florence (34th Inf.Div.)] The Germans, who were retreating along prearranged lines of resistance, offered light resistance. The 34th advance was mostly hampered by mines and booby traps, and by the rough Tuscan terrain. As had usually been the case during the long advance up the Italian boot, it was again a matter of gaining hilltop after hilltop, and movement took the form of long foot marches for the tired GI’s. The advance was greatly aided by Italian partisans, who guided the American troops, and assisted in the capture of German prisoners. About one hundred Partisans joined the 2nd battalion in this capacity, which was a new experience for the GI’s, since organized partisan activity was not common south of Tuscany. After liberating Campiglia, the advance of the 2nd battalion continued through San Vincenzo, Castagneto, and Bibbona, small picturesque towns, which nowadays have become summer resorts for tourists. For their liberation, 55 soldiers of the 34th Division paid with their life. Sometimes objectives were taken without a fight, some others the retreating Germans offered stiff resistance. The Germans were putting up delaying actions, as they gained time to prepare their main line of resistance south of the Arno, along the Cecina river about twenty miles south of Leghorn. Here, they were determined to resist in strength, making good use of self-propelled guns, pillboxes, and dug-in emplacements covered by extensive minefields. North Apennines, September – November 1944The Gothic Line was a belt of fortified passes and mountaintops extending in depth along the Apennines Mountains from the Ligurian Sea to the Adriatic coast. Due to terrain features, the weakest points in the line were the mountain passes north of Florence and the Adriatic coast. US troops were given the task of breaching the line in the Apennines, and the 34th Division was assigned the task to carry out a covering attack in force west of the Futa pass, distracting the Germans away from the Giogo Pass area, where the 91st Division was to achieve the real penetration with the aid of the 85th Division.

II Corps Attack on the Gothic Line (CMH) The 133rd regiment had the tough mission of breaching the German defenses along the Calvana hill-mass, a long ridge with heights up to about 3,000 feet running north from the Tuscan plain between Prato and Calenzano up to the Apennines divide at Montepiano. Typically, for the Italian campaign, the terrain consisted of numerous mountain peaks, streams, deep valleys, broken ridges, and rugged spurs, all offering excellent defensive positions to the enemy. Although large numbers of troops were involved on both sides, small unit actions predominated and rarely were units larger than a battalion engaged at any one time, as the compartmented terrain eroded the Allies advantage in manpower At 0530 hours on 11 September, the attack started, with Pvt. de Lama’s 2nd battalion on the right of the regimental front. The 133rd was again the point unit of the main Fifth Army effort, and German resistance was determined, notwithstanding heavy air and artillery support and the thorough preparation for the attack. For a period of nine days from 12 to 21 September 1944, the 2nd battalion was in almost continuous contact with the enemy, assaulting pillboxes and well-defended bunkers, protected by wire, extensive minefields and lanes of fire, or resisting German counterattacks. The mountainous terrain also hampered supply. Hundreds of mules and as many Italian military muleskinners were used by the 133rd, and four to five mules were lost each night due to falling off the steep cliffs and narrow trails in the dark. Pvt. de Lama was among them, having received his second wound in action since his transfer to the 133rd Infantry. He was wounded on 15 September, when G Company was attacking along the Calvana hill-mass towards the saddle south of Poggio Torricella (Hill 791), after having survived unscathed G company’s toughest fight the previous day. As for his earlier experience, there is no information on his wound and recovery. We do know that throughout the battle the evacuation of wounded was extremely difficult. Mountain trails were often impassable even to mules and, for the most part, mined and covered by enemy machine gun fire. Litter carrying parties often could only move at night, and necessitated all personnel available from all units of the division not actually engaged on the front lines. Local partisans and civilians lead the way at night over the badly known trails and through the rough terrain in the area. At one point, litters relay chains were established to cover the approximately six miles from the front lines to the waiting ambulances, and litter bearers were kept working around the clock to the point of exhaustion. Administering aid to the wounded was also a difficult task. The 2nd battalion aid station was at times located in a gully near a totally ruined village, amid a heavily mined area, and had to work in complete darkness. On 28 September, the 133rd was transferred close to Montecarelli, a movement of about fifteen miles along dangerous and rough mountain roads, the cold rain and strong winds all but freezing the soldiers riding in open trucks. The expected period of rest and rehabilitation was cut short almost immediately, and by the end of the month, the 133rd found itself near Madonna dei Fornelli, ready to attack in force the German strongpoints in the Mount Venere area, north of the Raticosa pass.

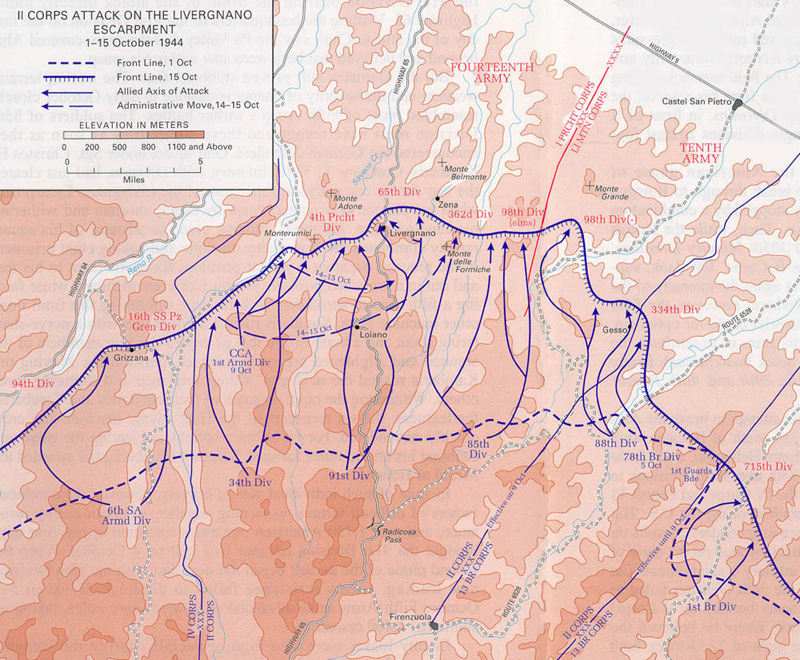

By the end of October, the stiff German resistance, compounded by munitions and shipping shortages, troop exhaustion, the lack of replacements, and the rapidly deteriorating weather conditions would compel the Allied High Command to stop the offensive short of its objective. The offensive failed, but between the beginning of the assault on the Gothic Line in early September and 26 October 1944, the US II Corps divisions suffered more than 15,000 casualties. In the 34th alone, more than 107% of rifle company officers became casualties in the same perid. So it was that on 30 September 1944, cold and drenched by the unending rain, the 133rd infantrymen walked the final miles from the detrucking point to their assigned positions in a sea of mud. At 6:00 a.m. the following day, the men in Company G started the attack, covering the left half of the regimental sector, against light opposition at first. However, German reaction stiffened during the day. The 2nd battalion struggled to gain hold of key terrain features, which changed hands several times. Company G lost 7 KIA’s in two days of fighting, mostly caused by German artillery fire, whose effect was made more deadly by the rocky ground, which added to the fragmentation effect of artillery shells. Mines were plentiful, and the mud hampered tank support. Early on 3 October, the 2nd battalion moved to the rear for a short rest, but on the morning of the following day, they were alerted again to spearhead the 133rd attack towards the town of Monzuno, which was liberated after a stiff fight on the night of 4 October, at the cost of another KIA in Company G. Still the attack went on under the unceasing rain, which stopped all vehicles movement and put engineers troops under severe strain. When the 2nd battalion was finally relieved on the night of 7 October 1944, it had suffered 32 KIA’s since the beginning of the month, 8 of which in Company G. On 11 October the whole 133rd regiment was relieved for a four-day rest period. The men could take hot showers, get haircuts, change underclothes and uniforms, and enjoy hot meals. Mail from home was distributed and a few soldiers and officers were sent to Florence at the Fifth Army Rest Center and Rest Hotel. By dawn of 17 October, the 2nd battalion had succeeded in getting on the southern ridge of Mount Belmonte, against heavy enemy small arms fire. With daylight, however, enemy tanks started firing on the exposed troops, and the 2nd battalion situation became desperate. Helped by the fog, which hampered observation and artillery support to the attackers, the Germans counterattacked in force, supported by tanks. Surprise was complete, and the advance elements of Company G were surrounded by the Germans, resulting in the capture of three officers and about twenty enlisted men. By the end of the month, the weather conditions steadily deteriorated. Roads and trails were mostly impassable, vehicles were wrecked or bogged down in the mud, and often not even the mule trains could bring the needed supplies to the front lines, nor help in the evacuation of the wounded.

The II Corps attempt at reaching the Po Valley was coming to its unsuccessful end. The troops consolidated positions and tried to gain limited objectives. Mount Belmonte having been secured, the 133rd adopted a substantially defensive stance. Taking part in the October offensive cost the 133rd regiment its largest monthly count of casualties for the whole Italian campaign, with 151 dead, 474 wounded, and 84 prisoners of war. Against these casualties, the regiment received only 185 replacements, and its effective strength at the end of the month was more than four hundred short of approved tables of organization. After a few days, the battalion was back into the lines, engaging in patrolling activity and reinforcing defense positions in preparation for the next phase of the campaign. Mines and barbed wire were laid, overhead shelters were built, reinforced with sandbags, timber, and corrugated iron, and gun emplacements erected with the help of unusually clear weather. German artillery fire was not intense, as the two armies settled down into static warfare. Also, all Italian civilians in the forward areas were evacuated by trucks and sent to safer locations. Altogether about 350 people were moved, including many children. Under the cover of night on 11 November 1944, the weary 133rd soldiers traded all weapons and ammunition, except personal weapons, with their comrades of the 135th Regiment, and left for Montecatini Terme by trucks. Picked by the US Fifth Army as a rest and training center for war weary combat troops, the city had already been used for similar purposes by the Germans until the summer of 1944. Tired soldiers could find relief in Montecatini’s luxurious bathing establishments, parks and gardens, and sleep in its more than 200 hotels, with electricity, running water, and fully equipped toilets and bathrooms. The town was substantially untouched by war, even if wartime conditions of course had an effect on the scarcity of goods displayed in its many shop windows. Soldiers could rent horse carriages with drivers, or shop around for Christmas gifts to send home. Mostly, however, they enjoyed the hot sulphur baths at Montecatini Terme’s famous establishments. The well-housed American Red Cross Club provided a tailoring shop, as well as reading and game rooms, a bar, and movies and stage shows. Also, the 133rd had its own reserved Italian photographic studio, where soldiers had their portraits taken to mail home.

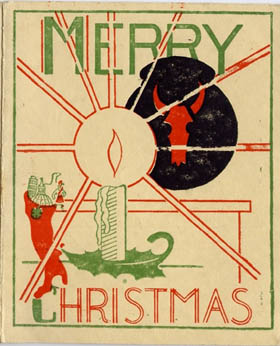

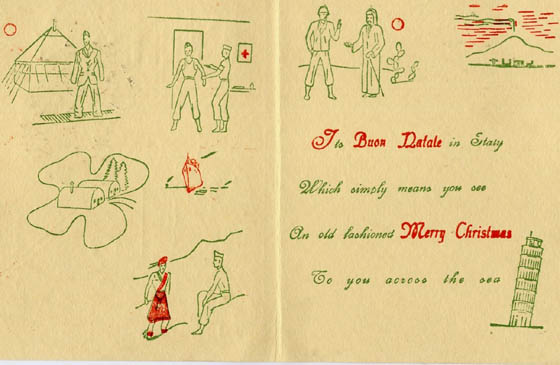

34th Division Christmas Card, Christmas 1944 (private coll.) Several men spent a few days in Florence, while many others received awards, decorations and promotions. Fifth Army commanded General Clark personally awarded many of these at a ceremony on 16 November. Christmas cards, for mailing to the States, were distributed to the troops on 17 November, and religious services were held daily.

Maybe a more welcome visit was that of several war correspondents and photographers from the Army magazine “Yank” and from the “Stars and Stripes” Mediterranean staff, the Fifth Army Public Relations Section, as well as from commercial news services, including the BBC, who spent several days in Montecatini Terme gathering material for stories about the 133rd soldiers. Observations posts were established and existing positions reorganized and strengthened, the assigned mission being to carry out the active defense of the area in preparation for the next strategic offensive, which at that stage was planned for December 1944, but would later be postponed until April 1945. Pvt. de Lama and his comrades in the 2nd battalion were assigned defensive positions on the heights northwest of Livergnano, running from i Gruppi through Lucca to Guarduzza, where the 1st battalion sector began. Go to the Map of the Front-line Positions of the 133rd Infantry Regiment, 23 November 1944] November 23, 1944, Thanksgiving Day, was relatively quiet. During daylight hours, the customary artillery duels took place. Late in the afternoon, the early sunset preceded the usual reconnaissance activity, with patrols on both sides probing the enemy lines. At 6:20 p.m., while on the lines at the Company G positions, Pvt. Ricardo de Lama was hit by small arms fire and died, struck by a bullet out of the dark.

After Ricardo de Lama’s death, his comrades in Company G carried on with their job through the winter, alternating periods of frontline service with rest, training, and defensive work in the rear, being lucky enough to spend Christmas in Montecatini Terme. They then participated in the spring offensive entering Bologna on 21 April 1945, and pursued the Germans all through the Po Valley and up to Ivrea, near Turin, in the Piedmont region of Italy. One Company G staff sergeant would die in January 1945 in a road accident caused by the precipitous terrain and winter conditions, and four privates would be killed in action in April 1945, the last death casualties in the company before hostilities ended in Italy on 2 May 1945. In nearly six months of service in Italy, Ricardo de Lama was wounded in action twice before his luck finally ran out. Aside from that, we do not have much information on his time in Company G. Depending on the seriousness of his wounds, or because of other circumstances we have no knowledge about, he may have been away from his unit for unknown periods. His award of the Combat Infantryman badge on 15 July may suggest he was with the regiment at the time. We do know, however, that he saw enough combat to be wounded twice and loose his life, and that is all we need as undisputable and everlasting testimony to his courage and his sense of duty and loyalty to his adopted country and his fellow comrades. We like to believe, though, that he might have shared with his fellow soldiers that common experience as a moment of due recognition for their sacrifices and a special way to celebrate his thirty-first, and unknowingly last, birthday. * The 133rd Regiment’s monthly reports, on which this story is also based, are available online at http://www.34infdiv.org/history/133narrhist.html thanks to Mr. Patrick Skelly, historian and secretary-treasurer of the Tri-state Chapter, 34th Infantry Division Association. His highly recommended website is an invaluable resource on the history of the 34th Infantry Division in World War II. |

| [Welcome - Benvenuti] |

Pvt. Ricardo de Lama y Martin, ASN 32996907, was inducted on 10 August 1943 at Camp Upton, NY. The son of a Spanish couple who had left Segovia to settle in Cuba at the turn of the century, at seventeen he had joined his brother in New York City, starting a career as an airplane pilot in acrobatic and stunt shows. Upon drafting, the Army proposed him to become a glider pilot, but he refused and was assigned for basic training at Camp Fannin as part of A company, 5th Training Battalion.

Pvt. Ricardo de Lama y Martin, ASN 32996907, was inducted on 10 August 1943 at Camp Upton, NY. The son of a Spanish couple who had left Segovia to settle in Cuba at the turn of the century, at seventeen he had joined his brother in New York City, starting a career as an airplane pilot in acrobatic and stunt shows. Upon drafting, the Army proposed him to become a glider pilot, but he refused and was assigned for basic training at Camp Fannin as part of A company, 5th Training Battalion.